Total 33 PostsDeveloperIsn't "comprehension" more important for developers now?

I often have a thought when I see developers these days. Problem-solving is done very quickly with AI. But they are not interested in what happened before. Why was it made this way, What was the business context, They don't ask or try to listen to why the existing code is in this form. Even not only code written by others, I was quite surprised to see them applying code they created with AI without properly looking at it. In one of the projects I experienced, There were cases where very inefficient and illogical code was included due to business requests. That was not a result of the developer's skill, but of the situation and requirements at the time. It was code like a "field artifact" that accumulated history. But these days, the attempt to understand such context is disappearing. "Existing code is strange → Rewrite it with AI" This formula is repeated too easily. The problem is that the newly written code, The moment it breaks the existing business logic or operational flow comes more often than expected. AI helps with implementation. But it doesn't tell you why it became that way. What is becoming more important for developers now is not coding speed or Ability to read existing systems An attitude of trying to understand strange code "before fixing it" The ability to think and connect history with business context Aren't they the same thing? As for how to use AI, honestly, you can just ask the AI. However It doesn't substitute for the ability to understand existing content. Future developers Will it be more important to "understand well" rather than "how quickly you can code"?2026.01.31 Thawing

ThawingThe Real Reason a Developer Missed a Deadline: Frozen Pipes

It was a certain day. One of the developers on our team suddenly started acting strangely. He was usually quiet but always got things done precisely, but then, Schedules kept getting pushed back Commits were sparse He spoke even less His expression in meetings was vacant At first, I had the usual suspicions. “Is he stuck technically?” “Is he having trouble concentrating lately?” “Could it be burnout…?” So, I made the typical manager move. “If you’re stuck on anything, let me know.” But the answer I got was completely unexpected. “Sir… my home’s water pipes froze.” …What? “I couldn’t shower… couldn’t even use the restroom properly… I was completely out of my mind.” At that moment, I realized. This person wasn’t stuck on code, he was stuck in life. What we often mistake When a team member is struggling, we usually interpret it like this: Is it a lack of skill? Is it an attitude problem? Has their sense of responsibility decreased? But sometimes, reality is truly simple. The reason a developer can’t meet a deadline might not be the difficulty of the algorithm, but the difficulty of the restroom. Conclusion: The problem wasn’t the code, but the person From that day on, I became convinced. When schedules are delayed, instead of asking “Why couldn’t they do this?” we should first ask, **“Are you okay lately?”** Development is done with the head, but the head ultimately operates on top of life. If the water pipes burst, the sprint bursts too.2026.01.23 AI Silo

AI SiloThe real debt that arises when AI develops too quickly

2026.01.19PlanFocusing only on the plan resulted in an unwanted product that was just tailored to the schedule.

So What Should We Do Now: How to Switch to “Execution Management” When I worked as a development manager at a startup, the thing I repeated the most was “making plans”. Business schedules came first, development plans were made to fit those schedules, and from then on, it was a structure of struggling every day to reach the goals. But at some point, something strange starts to happen. The team stops building the product and starts becoming optimized for making excuses to keep the plan. “Documents explaining why the schedule was delayed” “Post-mortem reports saying it couldn't be helped due to too many risks” “Re-planning the plan to make up for it next week” In the end, the result is similar. The schedule was met, but a product no one wants comes out. The Problem Is Not the ‘Plan’, But the ‘Absence of Intent’ Plans are necessary. But plans cannot replace execution. Problems that occur during execution cannot all be predicted at the planning stage. But the bigger problem lies elsewhere. When you start running solely based on the schedule, the team's interest shifts from “What should we build” to **“By when must we finish”**. From this moment, the development team and the business team stop running towards the same goal and start colliding with different orientations. Business wants “what the customer needs” Development wants “to meet the schedule” Neither side is wrong. It's just that the standards they look at have changed. And in teams where only the schedule remains, misunderstandings eventually pile up. “The dev team has no business understanding” “The business team just doesn't know development” Actually, both are only partially true, but the core is this. We only agreed on the schedule, we never agreed on the intent. The Development Team Cannot Make a Product That Satisfies the Market “Alone” One thing must be made clear here. It is difficult for the development team to read the market, analyze customer needs, and derive the “correct product” on their own. And the moment you shift that responsibility to the dev team, they choose one of two things. Become a team that doesn't listen (Overturning product planning) Become a team that just does what they are told without thinking (Only meeting the schedule) Both fail. What's important in a startup is not “Let's make the dev team build a product that satisfies the market,” but for the dev team to understand the business intent and become a team that turns that intent into the best implementation. Business takes responsibility for the market, development takes responsibility for implementation, but **a structure where the intent is aligned as one** is needed. So What Should We Do: 5 Steps of Execution Management (Intent-Centric Version) 1) Treat Plans as ‘Hypotheses’, Not ‘Contracts’ Many teams run plans like final versions. But a plan is a hypothesis. A plan is an estimate that “if we do this, it will work” Execution is the process of proving “actually doing it showed it was right/wrong” The moment you operate a plan like a contract, the team starts making distorted decisions to meet the plan. ✅ Practical Application Separate **“Fixed Schedule” and “Variable Scope”** on the timeline Keep the milestones, but leave the implementation scope adjustable 2) Set Goals Based on ‘Intent’, Not ‘Schedule’ Goals in schedule-centric organizations are usually like this. Login feature complete Dashboard 1st draft complete Payment API integration complete This is a task list, not a purpose. Intent-centric goals look like this. “Make sure signup conversion doesn't break” “Make the user move immediately to the next action” “Do not block the flow where payment occurs” In other words, the goal becomes not the feature, but implementing the flow the business wants. ✅ Practical Application Change the sprint goal sentence like this ❌ “Develop Feature A” ✅ “Implement Business Intent A, and verify success criteria” Here, the success criteria doesn't have to be the market, but **the business intent criteria (conversion, flow, data, operational feasibility).** 3) Don't Find Risks in Meetings, Reveal Them Quickly in Execution Execution management is ultimately a battle against risk. The moment you look for risks in a meeting, risk becomes an argument, and the schedule becomes a defense. Risks are only seen when you get your hands dirty. ✅ Practical Application: The 48-Hour Rule If there is a “vaguely difficult” task, do the work to just verify the risk within 48 hours first. API Integration → Try connecting just minimum call/auth Performance Worries → Check bottlenecks with dummy data Screen Ambiguity → Check reaction with prototype Doing this becomes grounds for decision-making, not an “excuse”. 4) Manage “Blocked Points and Decisions”, Not “% Progress” The phrase most used by plan-centric teams: “We are currently 70% done.” The reason this phrase is dangerous is that hell might exist in the remaining 30%. Execution-centric management looks at it like this. Where is the blocked point right now? What decision is needed? Who needs to decide and when? ✅ Practical Application: Daily 10-Minute Checklist What is the one thing blocked today? What decision is needed to break through it? Who is the person to decide today? Sharing just these three drastically reduces misunderstandings between business and dev teams. 5) Keep the Schedule, But Do Not Keep It While “Damaging the Intent” If you rush the schedule, abandon the intent, and just fill in the features, the result is this. An unwanted product fitted to the schedule What's more fatal in a startup is not a product coming out late, but a product that came out fast but is different from the business intent. ✅ Practical Application: Priorities When the Schedule Collapses Scope Adjustment (Maintain Intent) Implementation Simplification (Maintain Intent) Launch Schedule Change In other words, the schedule is adjustable, but the intent must not be broken. Conclusion: Not “Schedule”, But “Intent” Binds the Team Together If we focus on the plan, we can become a “team that keeps the schedule”. But if we focus on execution, we become a “team that implements business intent”. And for business and dev teams to move as one team in a startup, what is ultimately needed is this. Not the schedule, but Execution Management Aligned with Intent If you run only with the schedule, business and development create constant misunderstandings while having different goals. Conversely, if you share the intent, even if the schedule shakes a little, the confidence that you are looking at the same goal remains. That is what keeps the team from collapsing.2026.01.12 TPM

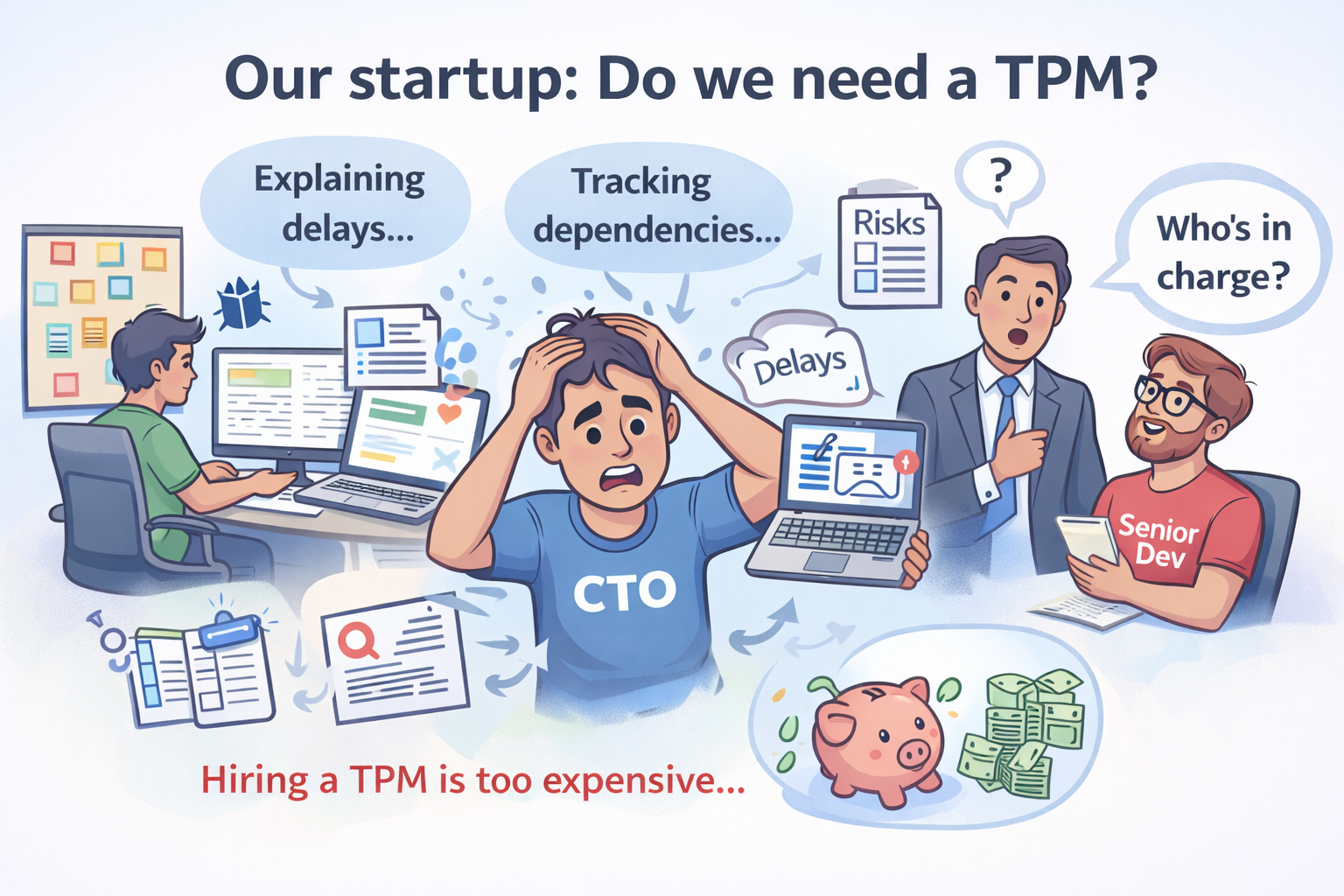

TPMHow can a team function without a TPM?

A New Solution Through BCTO and Aline.team When the topic of TPM (Technical Program Manager) arises in early-stage startups, the same question always follows: “Do we need a TPM?” And then, a realistic answer emerges: “We need one, but it’s difficult right now.” This article discusses why the TPM role exists and what changes when their responsibilities are broken down and implemented through systems instead of people. We will also explain where BCTO and Aline.team fit into this process. Why Was a TPM Needed? A TPM is not just a simple schedule manager. While a PM focuses on “What should we build?”, a TPM is responsible for the following questions: How is this work progressing? Who is becoming a bottleneck? How do technical decisions impact schedule and risks? How are the dependencies between multiple teams connected? As organizations grow and systems become more complex, these questions naturally converge on one person. That person is the TPM. This is also why TPMs are crucial in large corporations. A TPM is the person who connects technical and organizational complexity. But Why Is It Difficult for Early-Stage Startups? The challenge lies in the reality of early-stage startups. Experienced TPMs come with a high cost. The smaller the team, the more disproportionate the management burden becomes. Ultimately, many decisions rely on people’s experience and memory. Therefore, in most early-stage teams, the CTO or tech lead takes on the TPM role in addition to development. The problem is that this structure doesn't last long. Developers increasingly become coordinators, and while coordination increases, the basis for decisions becomes unclear. Breaking Down the Role from People to Systems Here lies a crucial shift in perspective: Instead of asking, “Should we hire a TPM?” ask, “What structure can handle the tasks a TPM performs?” If we divide the TPM's responsibilities, there are broadly two categories: Observing and explaining Facilitating coordination and decision-making Do these two areas necessarily require a person to handle them entirely? BCTO: Systematizing the TPM’s ‘Observation and Visibility’ BCTO automates the observation and reporting that TPMs do daily, using data. Based on actual Git commits, PRs, and issues, it shows “What is currently in progress?” and through developer work patterns and flows, it explains “Why did it slow down?” It transforms schedule delays or excessive optimism into evidence for proactive measures, not post-hoc analysis. The important point in this process is that it is about explanation, not evaluation. It doesn't show who did well or poorly, but rather what structures and flows led to certain outcomes. While a TPM would provide explanations through meetings and documents, BCTO offers continuously updated data. Aline.team: Supplementing the TPM’s ‘Coordination and Decision Support’ Aline.team goes a step further. The questions that TPMs often found most challenging are typically: Should a senior or junior developer handle this task? Is the current bottleneck technical or communication-related? Why does team speed vary with the same number of people? Aline.team learns individual developers' development patterns and strengths, analyzes task types and team situations together, and aims to answer questions like: “Who is the most rational choice to take on this task?” “Why was this schedule predicted this way?” “Where should intervention occur to speed up the overall flow?” This is less about making decisions for you and more about supporting decisions to make them explainable. So, Do BCTO and Aline.team Replace TPMs? To be precise, no. These two products are not tools designed to eliminate the TPM role. Instead, they enable the following: Teams to function without a dedicated TPM. Existing TPMs to focus on more critical decision-making. It creates a structure where systems handle 70-80% of the tasks a human TPM would perform, allowing people to concentrate on the remaining 20-30% of true judgment and responsibility. In One Sentence TPM is a role, and BCTO and Aline.team turn that role into a scalable system. What early-stage teams need is not perfect consensus or more coordination. A clear understanding of who makes decisions. The ability to explain why those decisions were made. A structure where accountability for outcomes is not blurred. When that structure is maintained, experience becomes a strength, and the team accelerates.2026.01.08 Code quality

Code qualityCode quality and technical debt

And when should we clean up

When talking about development with startup CEOs, I often see them using “code quality is low” and “too much technical debt has accumulated” as almost the same meaning. However, these two are not the same. If you don't understand the distinction, it becomes difficult to judge when to sprint and when to clean up. Difference Between Code Quality and Technical Debt Code quality is a story about the current state. Can other developers understand this code? Is it predictable where it will break when modified? Can the current team take responsibility for and operate this code? On the other hand, technical debt is a story about future costs. Because choices were postponed now, a state where more time and resources must be spent later A structure where the burden increases every time a feature is added To summarize, it can be said like this: Code quality is the state of now, and technical debt is the future burden that state will create. When code quality drops, technical debt accumulates easily, and as technical debt accumulates, improving code quality costs more. The two are close to a relationship that feeds each other. So the Question CEOs Ask Most Often When I talk up to here, there is a question that almost always comes up. “Then when should our team clean up technical debt and raise code quality?” Answering “always” doesn't fit reality, and saying “not now” only increases anxiety. So I usually suggest one criterion for judgment. One Practical Criterion Is our development team's development history stable enough in function and operation that there are no problems with the service's business deployment even if there are no major changes in production for at least 6 months? If you can answer “yes” to this question, it is highly likely that now is the time to clean up technical debt and raise code quality. This criterion is not a development perspective but a business perspective criterion. Even without adding more features right away, customer response and operation are possible, and sales or service expansion discussions do not stop Only when there is this much breathing room does the cleanup work have meaning. Why 6 Months? 6 months is not a technically magical number. However, in startup reality, it is quite a realistic unit. 3 months is often too short for problems to surface, and 12 months is often when temporary fixes have already become the structure 6 months is the minimum time to judge “is this code holding back the business right now?” One Important Caveat When using this criterion, there is a sentence that must always be used with it. “6 months is not a fixed rule, but a standard to judge whether our team has a ‘breathing interval’ to clean up technical debt.” Without this sentence, the conversation immediately flows like this: “Why 6 months?” “Our service is 4 months old?” “Is 12 months not okay?” Arguments surrounding the period number solve no problems. What's important is not how many months, but whether we can catch our breath for a moment. Adding One More Thing If you have decided to clean up technical debt, you must be able to answer the following questions. What do you intend to change? Why now? Who is responsible? Cleanup that cannot be explained mostly creates another debt. Improving code quality should not be done “because we want to be neat,” but a choice made to protect future speed. In Conclusion Technical debt is unavoidable in startups. The problem is not the existence of debt, but running without knowing when you are in a state to pay it back. If you have started talking about code quality, the signal might have already arrived sufficiently. What is needed now is not the courage to slow down, but a standard to judge when cleanup is possible. The clearer that standard becomes, the code, the team, and the business will look in the same direction.2026.01.06 Code quality

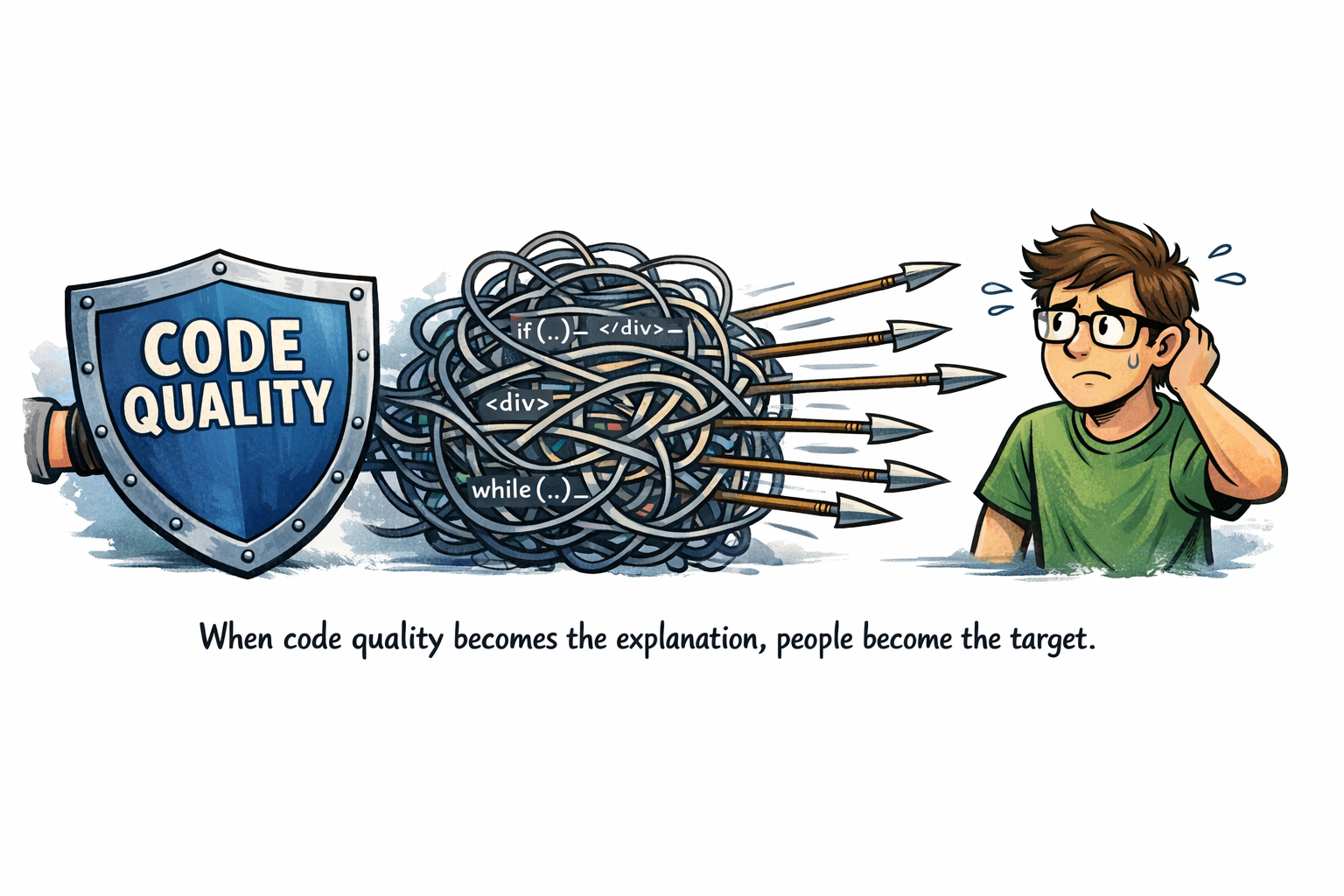

Code qualityWhen the term "code quality" comes up in a startup,

Are we really looking at the same problem? When startup CEOs come to me for advice on development team issues, there's one phrase they use more than any other. “I think the code quality is low.” “That's why development speed is so slow.” “Maintenance is almost impossible in this state.” “Further development is difficult in this condition.” At first, we naturally formed this hypothesis: Perhaps they have a developer acquaintance, and that acquaintance used these terms. However, as we repeatedly solved similar problems, a strange feeling began to emerge. Why do the CEOs of such small organizations bring up a rather technical issue like ‘code quality’ to me? A Recurring Pattern Began to Emerge As I continued to consult, I noticed common situations that appeared quite frequently. Initial development completed by an external vendor Subsequently hired junior developers internally Attempting to start operations and further development And then the words appear “This code has such low quality that a senior developer needs to redesign it and rebuild it from scratch.” At first glance, this statement sounds very reasonable. However, upon closer inspection, it often points to a slightly different problem. “Code Quality” Sometimes Becomes a Defense Mechanism When junior developers take over code developed by external vendors for operation, they often feel a much greater burden than expected. Difficulty understanding the overall structure Lack of context on why it was designed that way Side effects occurring even with minor modifications Unclear scope of responsibility In this situation, it's not easy to say, “I don't have enough experience yet, so I need more time.” Instead, a much safer phrase emerges: “It’s because the code quality is low.” This statement shifts the cause from personal capability to an external entity: the code. Even if unintentional, it effectively becomes an excellent defense argument. The problem arises the moment this statement is communicated to the CEO. The Arrow Always Flies in the Same Direction From the CEO's perspective, it sounds like this: “The current team can’t handle it.” “We need to hire a new senior developer.” “The development so far has been flawed.” From that moment on, the focus of the problem shifts from the structure or process to people. Who failed? Who is lacking? Who needs to change? And that arrow usually points towards the same developers. So, I Often Advise This When the topic of code quality arises, I often tell CEOs: “In the current situation, rather than rushing to hire a senior developer, it might be the better choice for the current team to take more time and continue with this code.” This doesn't mean the code is perfect, nor does it mean seniors are unnecessary. However, it rests on the premise that: The current difficulties are less about the quality of the code and more likely due to a lack of context, insufficient understanding, gaps in handover, and the common mismatch of roles and expectations in small organizations. Code Quality is a Result, Not a Cause This is especially true in very small organizations. Code quality is less about individual skill and more a cumulative result of the team's decision-making process, time pressures, and unexplained choices. Yet, we often summarize this complex issue with the single word “code quality.” From that moment on, the conversation stops, and responsibility merely shifts. Concluding This Article This article is not intended to blame junior developers, nor to criticize the CEO's judgment. However, one thing is clear: When the phrase “code quality is low” arises, it's worth taking a moment to re-examine whether it truly refers only to the code itself. Perhaps hidden within it lies an organizational issue that has yet to be articulated.2026.01.05 Development effort

Development effort3 months vs 5 days

Whose Word Should We Trust? This happened when I was working as a startup CTO. After designing a feature, I called developer A, who had been with the company for a while, and asked for an estimated completion time. The answer was "It will take about 3 months." I was from a development background and had gone through similar projects many times. Honestly, it didn't make sense. So, I called a newly joined developer and asked the same question. The answer was "It will take 5 days." This moment is a disaster for managers or executives without project experience. 3 months vs. 5 days. The difference isn't just a matter of opinion; it's a number that shakes up business schedules, resource allocation, costs, and investment timelines. So, who should we trust? Was Developer A Wrong? Not necessarily. Experienced developers often provide Requirement changes QA and communication costs Technical debt Post-deployment risks as part of a "realistic timeframe." The 3 months might not be "coding time" but rather "time to take responsibility if something goes wrong." Then, Was the Developer Who Said 5 Days Exaggerating? This is also not the case. The new developer might have been stating The requirements are fixed Ideal conditions Based solely on their scope of work the "pure implementation time." This is also true. If it were just about writing code, 5 days might be accurate. The Problem is the Standard, Not the People The real issue in this situation is not who is right. What standard was used for the estimate? What risks were included? How does it compare to similar past tasks? The problem is the complete lack of visible grounds for these questions. From a manager's perspective, there's no way to distinguish between a "slow developer" and an "exaggerating developer." Ultimately, they resort to gut feelings, and those gut feelings almost always ruin the project. What's Needed is Comparable Numbers To reduce this confusion, estimating development timelines requires at least the following: Actual time spent on similar features in the past Average deviation at the individual and team level Ratio of design to implementation, review, and deployment Impact of anticipated risks on the schedule In other words, instead of "This time it's 3 months" or "This time it's 5 days," everyone should be able to understand why that duration is estimated and how it compares to previous projects. Development Timelines are a Matter of Data, Not Gut Feeling Developers don't lie. They simply speak from different perspectives. The problem is the lack of a common language and metrics to explain these differences, and the burden always falls on the managers and the entire organization. It's time to ask "What can we use as a basis for judgment?" rather than "Whom should we trust?"2026.01.03 Development team

Development teamAI can accelerate development but also slow down the team

AI has now gone beyond being a tool that makes development easier, and has entered a stage where workforce reduction is being realistically discussed. In my experience, doing more work faster has certainly become possible. From code generation and test supplementation to refactoring suggestions, AI significantly boosts developer productivity. However, if you ask whether a non-developer can perfectly perform development tasks using only vibe coding, my answer is clear. “It is still very difficult.” The problem isn't simply about grammar or technical proficiency. The task of repeatedly making partial modifications without understanding the code is far more dangerous than one might think. Especially when working in a team of two or more, AI might become a tool that rapidly accumulates technical debt rather than increasing productivity. AI generates plausible code by referencing context, but it does not take responsibility for whether that code: Aligns with our team's design philosophy Respects the intent of the existing code Is a structure that is maintainable and scalable in the long term There is an actual case. Our team once hired a junior developer to work on a project. Lacking project and team experience, the developer focused on implementing immediate features rather than fully understanding the existing source code. With AI's help, features were built quickly, but the senior developer had to spend more time organizing the results to fit the team's code style and structure. Ultimately, to meet team standards, the design had to be supplemented, code rewritten, and the intent documented. What I felt during this process was clear. AI gives speed to the individual, but it can leave behind debt in the form of unaligned code for the team. In particular, apps built by junior developers alone with AI assistance might look highly complete initially, but often, the cost of modification skyrockets with even small requirement changes. I realized once again that technical debt arises not from the amount of code, but from unshared intent and context. So when a new developer joins the team, I feel that now, more than tech stack or speed, The ability to understand and accept team culture Experience writing code with collaboration in mind A mindset that considers the “next person” over “immediate implementation” have become much more important. If I were to consider hiring a junior developer again, I would probably ask this: Not “How well do you use AI?” But “How much have you respected others' code while working?” In an era where AI accelerates development, in teams where two or more people work together, human thinking and collaborative ability become the most powerful mechanisms to reduce technical debt. Therefore, I judge future developers not as people who create a lot of code, but as people who know how to create together.2026.01.02 Developer

DeveloperIn front of the request to find a "good developer," there are two things I always ask.

When a problem arises in development, I often receive requests like, “Please find me a great developer.” Each time, I almost reflexively ask two questions. First, “What kind of person do you consider a ‘great developer,’ CEO?” Second, “Are you perhaps building an operating system like Windows or macOS?” In most cases, they shake their heads at the second question. And then, a brief silence follows the first question. The True Meaning of a ‘Great Developer’ According to CEOs When startup CEOs say “great developer,” they usually don’t mean a top 1% genius developer. The person they truly want is typically someone like this: Someone who doesn’t escalate problems. Someone who can proceed without lengthy explanations. Not a monster who writes tech blogs all night, but Someone who understands our team’s context and moves forward with us. In other words, rather than “someone who writes code exceptionally well,” it’s “someone who makes work flow smoothly when working together.” Most Startups Aren’t Building ‘Operating Systems’ To be blunt, what most startups are building isn’t groundbreaking algorithms or the world’s first technology. Services centered around CRUD. Products that combine existing technologies. Early-stage projects where speed and direction are more critical. In such situations, what’s needed isn’t extremely outstanding individual technical skill, but rather a developer who operates stably within the team. Therefore, ‘Rhythm’ is More Important Than ‘Skills’ Of course, basic development competency is important. However, in a startup, other aspects are more crucial. An attitude of understanding the incompleteness of planning. An effort to read unspoken intentions. The rhythm with the CEO, designers, and other developers. Ultimately, what the CEO is looking for isn’t “a developer without problems,” but “someone who can handle problems together.” The ‘Great Developer’ I Speak Of Is Someone Like This So, I summarize it this way: A great developer is not someone with a flashy tech stack, but someone who makes work progress within our team. And such a developer is revealed not through a resume, not through GitHub stars, but through their rhythm with people.2025.12.29